Experts say that the Netherlands lags behind other European countries in the field of femicide prevention. Countries like Spain and Serbia are doing more to recognize and prevent the murder of women. Three experts explain why the Netherlands is lagging behind. “We mistakenly think things are going well.”

The case of the woman shot dead in Gouda has sparked discussion in the media about femicide. Femicide is the murder of a woman because she is a woman. This term can include various forms of murder, such as (ex-)partner murder or murder within the family. You can read more about the different definitions in this article.

In the Netherlands, we started relatively late in labeling this type of violence as femicide, says Pauline Aarten to NU.nl. She researches femicide.

For example, when a woman is murdered by her (ex-)partner, it is still too often seen as an incident that takes place behind closed doors. “In most cases, for example, domestic violence precedes it, and that is a problem that others do not like to get involved in. We then describe it as a ‘family killing’ or ‘partner violence’, but not as femicide or gender-related violence.”

That ensures that we unfairly dismiss femicide cases as incidents and that violence against women is not seen as a structural problem, Aarten continues. “By calling a spade a spade, people see how often it actually occurs.”

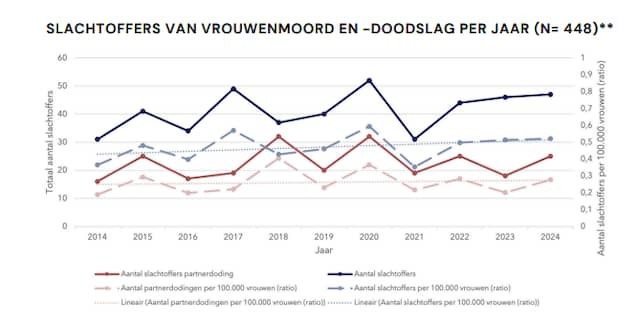

The figures show that femicide is indeed a structural problem. On average, a woman is murdered every eight days in the Netherlands. That is between forty and fifty cases annually. In the graph below you can see the numbers per year:

Police may inform woman about violent past of partner

Other countries, such as Serbia, started earlier with recognizing and naming femicide. For example, journalists have developed special guidelines for the media, with tools to better report on gender-related violence. This is done, among other things, to create awareness and to limit trauma for victims and relatives as much as possible.

In Sweden, care workers, among others, are trained to recognize signals of violence against women. Malta and Cyprus are frontrunners in the field of legislation. There, femicide is included in the Penal Code as a separate offense.

Spain is ahead in terms of keeping records. The country registers five different categories of femicide and researches the motives of the perpetrators. “That gives a good insight into the nature of the problem, which also contributes to better legislation,” says Britt Myren. She is a researcher at the Atria knowledge institute.

The Spanish police also have the power to inform women about the past of their partner if they have previously been convicted of abuse. In addition, a lot is done in Spain on prevention. Children are taught from a young age how to treat each other.

According to Myren, this is very important to nip femicide in the bud. “We see, for example, that sexist comments are accepted in the Netherlands. But it is a slippery slope that can lead to violence and even femicide if we do not learn that that is undesirable behavior.”

The Netherlands is slowly getting started

Myren is working on a project that focuses on preventing gender-related violence and sexual partner violence in the Netherlands. She mainly focuses on young people. “For example, we talk to them about their ideas about having a relationship and that controlling behavior is not healthy. You want to break that kind of thing during puberty.”

Despite the Dutch backlog in the field of knowledge and measures, things are getting better, sees Barbara Godwaldt. She is the initiator of the national Femicide Action Plan. The term femicide has been mentioned more and more often in recent years, she notes.

Among other things, the municipalities of Rotterdam, The Hague and Amsterdam have included measures in their municipal policy to recognize partner violence more quickly and to support victims. For example, in Rotterdam there is a special public prosecutor who is committed to limiting and punishing domestic violence.

“But we are wrongly inclined to think that we have everything in order in the Netherlands.” Godwaldt mentions as an example that the conversation about femicide often only starts again when a woman has been murdered, as is now the case after the murder in Gouda. According to her, there is also still a lot of work needed to properly implement the action plan, which she helped develop, in practice.

“The development of that took almost three years. Since an average of forty women are murdered annually, that has already cost 120 lives. So it cannot go fast enough,” emphasizes Godwaldt.

What is the Femicide Action Plan?

The plan was set up by various organizations and experts to prevent femicide and other violence against women from the government. The four main pillars are awareness, prevention, better signaling and supporting civil society organizations.