A man who died in Egypt 4,500 years ago had ancestors from North Africa and Mesopotamia. Researchers examined DNA from his skeleton and found the first genetic evidence connecting cultures from both regions.

The human remains were found in a tomb in Nuweirah, about 250 kilometers south of Cairo, the current Egyptian capital. The man was buried there about 4,500 to 4,900 years ago. 80 percent of his DNA comes from ancestors from North Africa, 20 percent of the DNA comes from Mesopotamia.

That is the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, around the current countries of Iraq, Turkey, Syria and Iran. The DNA research now also shows a genetic link between Egypt and Mesopotamia. The results of the research were published Wednesday in the scientific journal Nature.

In both areas, early human civilizations developed because of the fertile soil around the rivers. In Egypt this happened around the Nile.

The DNA research shows for the first time a genetic link between Egypt and Mesopotamia. There was already archaeological evidence that the two cultures were linked. For example, techniques in pottery were similar. There were also similarities in the cuneiform script of both areas.

New techniques used on skeleton found in 1902

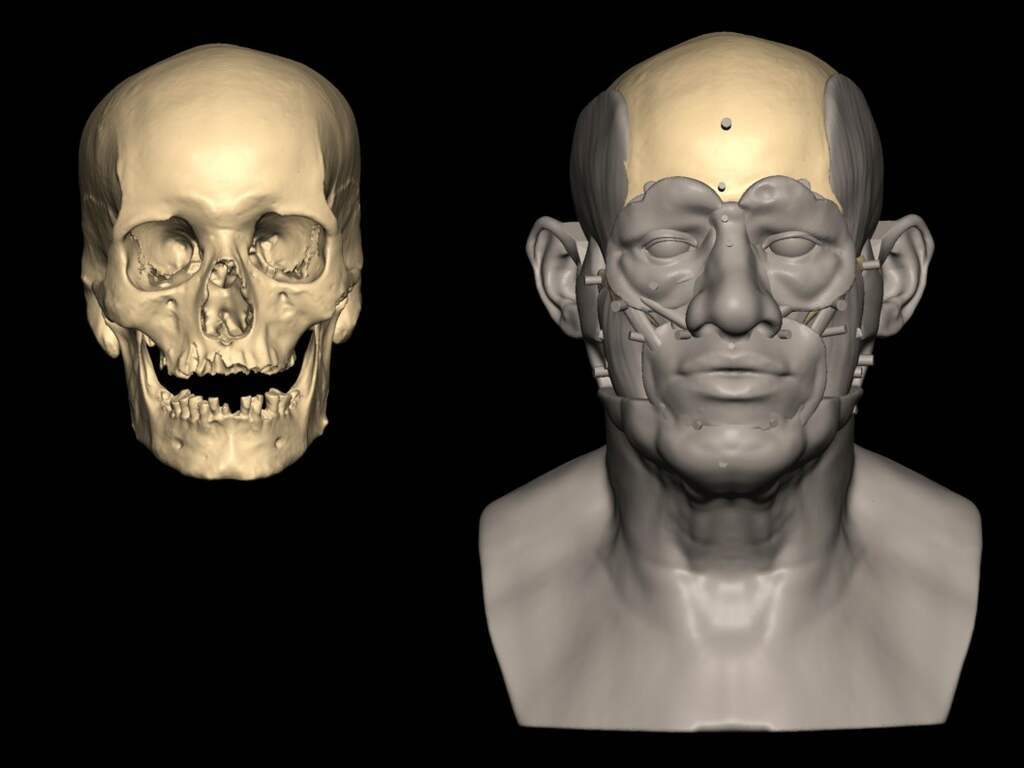

The skeleton was already found in 1902 and has since been in the World Museum in Liverpool, reports Science Alert. Using new techniques, scientists were able to accurately examine the man’s DNA from ancient Egypt. They were even able to find out the man’s daily diet: a mix of animal proteins and grains such as wheat and barley.

The man had reached about sixty years old, a considerable age for that period, and was about 160 centimeters tall. His tomb indicated that he lived in a high social class. But his skeleton also shows that he had done heavier physical work. That was not common in ancient Egypt among people with high status.

The man’s bones were longer than usual and researchers also found traces of arthritis, a form of rheumatism, in his foot. That combination is an indication that the man was a potter, says bioarchaeologist Joel Irish of John Moores University in Liverpool.

Regarding the higher status, Irish suggests a possible scenario: perhaps the man was exceptionally good at his work and therefore rose higher on the social ladder.