In the column The Greenhouse, climate reporter Jeroen Kraan writes weekly about what he notices. This week: a walk through the history of the Earth makes the astronomically large climate impact of humans clear.

I am standing in the Diemerpark in Amsterdam, but I imagine myself somewhere deep in the Milky Way, 4.6 billion years ago. A new star has just been created there, and planets are also being formed in the gas cloud around it. One will later be called Earth, although it is not yet blue and green at that time. It seems to have smelled like rotten eggs.

In the Diemerpark it smells like the first rain after a long period of drought. Petrichor is the beautiful name for that, I learn later. While my pants are still sticking to my legs after a poorly timed downpour, Merel van Meerkerk takes me on a Deep Time Walk. We are going to walk 4.6 kilometers, with each meter representing a million years of Earth’s history.

After only a short walk, the moon is created, and a few hundred meters further on we are in the middle of the ‘early bombardment’. Meteorites strike the Earth and leave behind the building blocks of life: carbon, water, minerals.

After less than a kilometer of walking, that is, 3.8 billion years ago, the first life arises. Van Meerkerk has brought a bottle of (non-alcoholic) champagne for the occasion, which I finish with my fellow walkers.

Coal arises over 25 million years

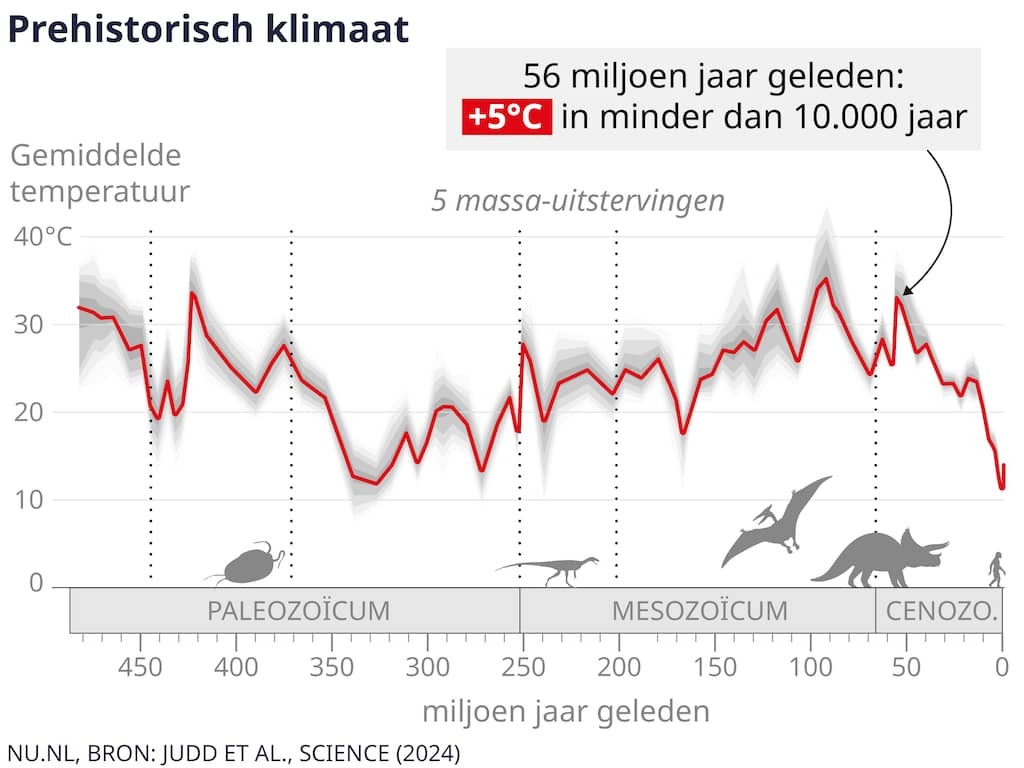

In the kilometers that follow, I learn an enormous amount about the history of the Earth and the gigantic (climate) changes that have taken place over the many millions of years. From the ‘oxygen crisis’ caused by a gigantic blue-algae bloom to the ‘snowball earth’ that almost wipes out all life (see image at the top) and the formation of the lichens that we still see sitting on the sidewalk.

A barge with mountains of coal passes on the adjacent Amsterdam-Rhine Canal. With 360 meters to go, Van Meerkerk says that this fossil fuel is created during the Carboniferous period, when large primeval forests arise and disappear again. It takes 25 million years: 25 meters of this walk.

Not much further on, the end is now in sight. But we are not yet at the emergence of humans, or even the dinosaurs. We reach the Jurassic Park era 200 meters before the finish. And only 3 meters before the end do the first hominids walk upright.

CO2 concentration increases in the blink of an eye

In the last meter, Van Meerkerk takes out a measuring tape. Homo sapiens is still not there, we have to move forward a few shoe lengths for that. At 30 centimeters before the end, the time has come: our species walks around on Earth.

The industrial revolution begins 0.2 millimeters before the end, a sliver of a fingernail. And that is where that coal from the Carboniferous period is massively set on fire. In doing so, humans are setting in motion a climate change that is rapidly changing the relatively stable climate on Earth.

The CO2 concentration in the air has increased by 50 percent in the last micrometers of the walk, to a level that last existed millions of years ago. The temperature will, as we know, inevitably follow.

Our impact is astronomically large

Earlier in the walk we heard what such sudden changes can do to the Earth: system shifts that suddenly change the planet drastically after a period of stability. Often with mass extinctions as a result.

“What we have seen in the past, we see coming back here. But now due to us,” says Van Meerkerk in conclusion. That makes this walk indeed very insightful. By walking this route, you notice how tiny ‘our’ part of world history is, but how astronomically large the possible consequences are.

“I hope that participants in this walk will feel a little more connection with the world around them,” says Van Meerkerk afterwards. She quit her job this year to give full-time climate training and workshops. She hopes that after the walk we will ask ourselves what we can do for this planet, with all the other life that has made our life possible.

“We can still do something to go back to a time when we are in balance with what lives on Earth,” says Van Meerkerk. “I have that hope. I plant a seed. It may not come up, but then I will have tried.”